In my previous post I took a somewhat critical look at artistic ‘greatness’ understood as a quality that sharply distinguishes ‘great’ artists and their works from ‘ordinary’ people and everyday life. For art to move us, does it necessarily have to rise above us? Does it have to be a work of incomparable genius? Does it have to be monumental? Or can it be small, banal, personal? Can it, quite simply, speak about love? I will now be looking at pictures by an artist who filtered his personal experiences through some of the most trivial and commonplace products of the visual culture of his time, transforming those trivial images into something intimate and full of life. This perpetual oscillation between general and singular, public and personal, was crucial to Bertalan Székely’s (1835-1910) representations of domestic life.

The collision between greatness and intimacy is a productive force in Székely’s oeuvre. Today, he is widely known as a history painter: his scenes from 16th-century battles against the Turks are familiar to the Hungarian viewer not only as artworks, but as illustrations in history books. They are certainly great: depicting turning points in history, they are monumental in their sizes and awe-inspiring in their compositions, often recalling religious imagery, as in the case of The Discovery of the Corpse of King Louis II after the Battle of Mohács. There is, however, another facet to Székely’s art, much less known today, but – as evidenced by his notes and sketches – considered equally important by the artist himself. Besides the great events and heroes of Hungarian history, Székely also aimed to depict moments of everyday life; scenes so general, so universal that – according to him – any person from any country would understand them. To achieve this, he planned series of lithographs narrating ‘typical’ human lives.

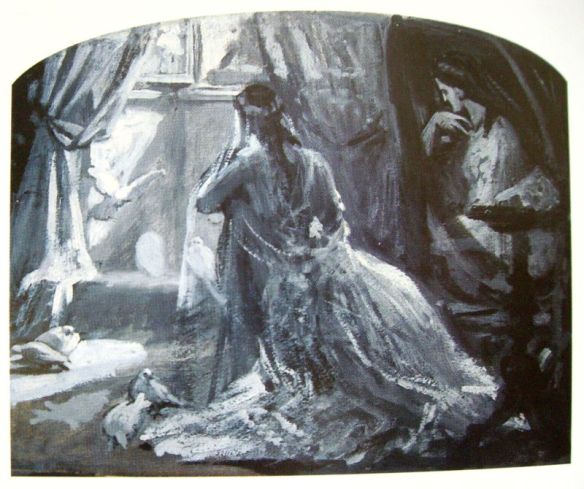

Bertalan Székely: The Bride, 1869-1870 (oil sketch for a scene from the series Life of the Woman; Hungarian National Gallery)

The retelling of these narratives has been made quite difficult by the fact that none of the series were ever lithographed. Székely’s preliminary sketches survive in many versions and forms, often separated from their original contexts. Art historian Éva Bicskei set out to reconstruct the series through meticulous research, finally publishing her results in a book.* She started out from a document preserved at the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Hungarian National Gallery, the so-called ‘diary of the young Székely.’ The ‘diary’ is in fact a scrapbook, which had first served simply to record the young Székely’s ideas during his studies, but was later gradually transformed into a sort of visual autobiography. Pasting drawings cut out from other sketchbooks into the ‘diary,’ Székely transformed it into a self-image-building account of his own artistic development. Following Székely’s death, some pictures were cut out and rearranged again.

After painstaking research, Bicskei succeeded in identifying the earliest drawings and notes. These show that as a fledgling painter, Székely was preoccupied with the implications of being an artist. Influenced by romantic notions of genius, he imagined the artist’s life and way of thinking as antagonistic to ordinary society. He jotted down lists of popular romantic novels about artists. These texts had a profound effect on him, as evidenced by the series narrating the lives of artists which he had sketched up in his diary.

Bertalan Székely: Scene from the Life of Caravaggio, 1859 (from Bertalan Székely’s ‘diary;’ Hungarian National Gallery)

There was, however, another subject which had grabbed the young Székely’s imagination, and that subject was love. In 1858, when carrying out some painterly commissions in Marschendorf (today Horní Maršov, Czech Republic) for the Aichelburg family, he met Johanna (Jeanette) Kuderna, an orphaned girl living on the Aichelburgs’ estate, and fell for her immediately. He soon had to leave – he commenced his studies at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in November 1859, and still had some commissions to complete beforehand. He did return to Marschendorf, however, in the next years, and not just once. Székely and Jeanette got married on 7 January 1861. The wedding was quick and hushed – Jeanette was already pregnant. Their son, Árpád, was born on 26 February 1861, which means the love affair had been consummated sometime in May-June 1860. Passion had taken hold of the aspiring young painter, turning him into a regular member of society: a man married with children. After the wedding, Székely went back to Munich for another 18 months, leaving his family behind, but finally, in late 1862, the couple settled in Pest, Hungary, for good. They subsequently had two more children: Ármin and Jenny. Székely was a respectable history painter and – from 1871 – a professor at the newly established Hungarian art school (a school that trained drawing teachers, but also provided foundational education for aspiring artists). As regards his public image, he was everything but a rebellious artist similar to the protagonists of the romantic novels he had read in his youth.

Those novels had inspired Székely to draw scenes from the lives of artists. At the same time, his love inspired him to draw scenes from everyday domestic life, as he imagined it. He started planning a series of drawings telling a deeply personal story – the story of Jeanette and Bertalan’s love and marriage. The series consisted of scenes from their courtship and from their future, married life, and was created as a gift for Jeanette. Therefore, Székely used the diary for preliminary sketches (identified by Bicskei as versions A and B of the series), but mounted the finished version (version C) into a new book. He then presented Jeanette with this album probably just before their wedding. Maybe not wanting to leave the remaining pages empty, he also created a fourth version (version D), adding it after version C.

Bertalan Székely: Scenes of courtship from the Series Drawn for His Wife, 1859 (from Bertalan Székely’s ‘diary;’ Hungarian National Gallery)

Bicskei’s comparison of the versions is fascinating and revealing. In turning his personal memories, experiences, and expectations into art, Székely made use of the imagery of (mainly French) popular prints depicting love and marriage. He relied on such precedents both when imagining scenes from their future marriage – events which had not happened yet –, and when drawing more personalised scenes from their courtship. In the case of the latter, Jeanette was probably reminded of real events she cherished in her memory, while the rest of the pictures constituted Székely’s promise of future marital bliss. He integrated his artistic profession – a profession that required him to spend much time away from his family – into his picture of ideal family life. Most of the story is set in the family home, and while some pictures refer to the man leaving and returning, the couple share the domestic space as equals.

Bertalan Székely: Teaching the Child to Pray, c. 1860 (Series Drawn for His Wife, version C, private collection)

Version D, however, presents a different picture. Again, Székely was adapting his personal story to widely known, stereotypical depictions of love and marriage, but this time those stereotypes visualised – more authoritatively than the ones preforming the previous versions – the prevailing notions of gender roles, and thus relations of power in society. The man is more pronouncedly depicted as an intellectual who spends his most productive hours away from home, while the woman is confined to the house, her duty being to nurture and support the man and his children. The house and the garden are not shared equally anymore – they are the woman’s realm. For the man, however, the same spaces now serve as a retreat, where he can rest after doing more important business elsewhere – and it is the woman’s job to make sure he can rest comfortably. Bicskei shows through many examples how this conception of gender roles was promoted by texts and pictures representing women – pictures like those which had served as models for Székely. The separation of gender roles was essential to the separation of the public sphere and the home, which was, in turn, an important element in the structure of modern society – then stabilising itself in the nation states of the 19th century.

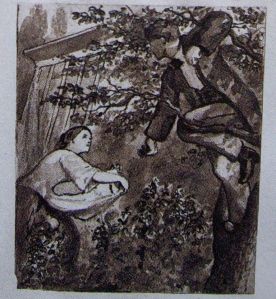

According to the worldview presented in version D, the role of the female is to support and foster male creativity. New ideas sprout in the man’s productive mind – the woman’s role is to help them grow. This role is embodied in the pictures showing the wife in the garden. But another picture – one that is unique to version D – is even more telling. The young man has climbed up a tree and is picking cherries, throwing them into the girl’s lap. She is standing under the tree, spreading her apron and waiting passively. Bicskei brings up many convincing analogies to prove that fruit picking was commonly used as an allusion to sexual activity in popular imagery of the time. New life is created by the man’s activity – the woman is there to receive and nurture it.

Bertalan Székely: Picking Cherries, after 1861 (Series Drawn for His Wife, version D, private collection)

The conception of their son, which had made it urgent for them to get married, had not featured in the first version of the series. It must have been one of the most poignant memories of their love affair, a cherished and very personal memory, but when Székely eventually did refer to it, he could only do so through a pictorial commonplace. In version D, he could mention it precisely because by then he had depersonalised the story to such an extent that it was no longer about Jeanette and Bertalan and their passionate, but illicit love affair – it was about a theoretical man and a theoretical woman and their symbolic and dull cherry picking.

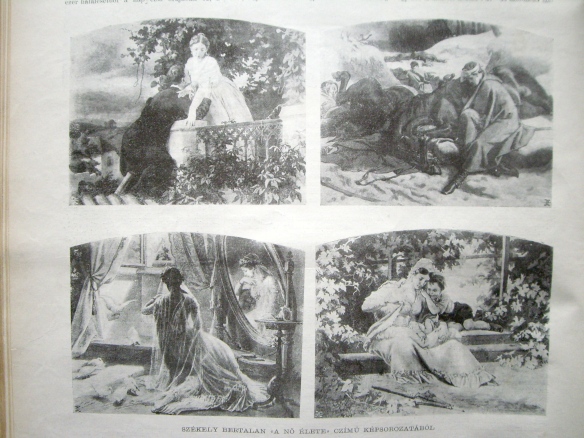

From version D, Székely only had to take one more step to create a series meant for the wider public. He planned and sketched a series of lithographs entitled Life of the Woman, partly using compositions from the series made for Jeanette. He planned to have the lithographs printed and distributed, but this plan was never realised. The series would have told the life story of a generalised Woman, beginning with courtship and ending with widowhood. The woman’s life was structured by her relationship to her husband. She is an exemplary woman – a supportive wife and nurturing mother, content with the domestic sphere assigned to her. Such exemplary life stories were widely distributed both in the form of texts and of series of images – as mentioned before, Székely had modelled his versions on such popular precedents. These narratives had a didactic purpose; they were often given to young girls as gifts before their marriage to help them become good wives. This leads us to a somewhat disappointing conclusion. When Székely presented the booklet, complete with version D, to his wife, he was declaring his love and giving her a personal, intimate gift. But at the same time, he was also declaring what he expected from her as a wife.

Bertalan Székely: Sketches for the series Life of the Woman (reproduced in the periodical Vasárnapi Ujság, March 18, 1900)

Székely cannot be blamed for using stereotypes to express his personal experiences. It is something we all do when trying to relate the singular events of our lives to others. Falling in love is a unique experience, and attempts to fit it into preexisting stereotypes are attempts at understanding and explaining it – to ourselves and to the world. The popular images and texts on which Székely had modelled his series were similar in their function to articles in today’s women’s magazines. How To Dress On Your First Date? How To Tell If He Is Really Into You? Besides perpetuating the prevailing gender roles just like their 19th-century predecessors, these articles also offer the illusion of being able to harness the irrationality and unpredictability of love. Ordered into neat lists like Ten Things You Should Avoid Saying On A First Date, the feeling that your life has suddenly started to revolve around someone you barely know seems less scary; it seems to be manageable. If others have survived it, so will you.

But of course it is scary, and of course it isn’t manageable. And you might not survive it. Before meeting Jeanette, Székely was a young artist preoccupied with his career, who idolised the solitary geniuses of the novels he had read. After succumbing to his desire and picking those cherries he became a family man; one half of a couple. He could not roam the world as his fictitious artist-heroes did. He wanted to rise up into the imaginary land of artistic fantasy, but was chained to everyday life by his earthly desires.

Bicskei concludes her book by showing how the motif of getting consumed by unconstrained passion permeats Székely’s oeuvre. First of all, he had planned another series of lithographs too: one that would have shown a negative example – a vain woman. The surviving sketches tell the story of a girl who – unable to control her lust and her desire for wealth – is seduced by a rich man and becomes his mistress. Her lack of control is subsequently punished: abandoned by her lover, she falls ill and regrets all her sins. Székely used correspondences between motifs and compositional structures to build coherence in his visual narratives, often creating pairs of corresponding images. In one picture, the mistress is stretching contentedly in front of her mirror, in her nightgown – she has obviously partied late and has nothing useful to do in the morning. In another picture, the fallen woman, stricken with illness, wakes up in front of her mirror only to be shocked by her own withered face.

Bertalan Székely: Scene from the Life of a Vain Woman, late 1860s (oil sketch for lithographed series; Hungarian National Gallery

Bertalan Székely: Scene from the Life of a Vain Woman, late 1860s (oil sketch for lithographed series; Hungarian National Gallery)

Thus, uncontrolled passion gets its just deserts, and everything falls into place again. But in other works cited by Bicskei, this is not so simple. Székely had painted many versions of Leda and the swan; works which were previously interpreted as boring academic compositions, but which Bicskei sees as visualisations of succumbing to passion. In the pictures, Leda is both seducer and seduced; the swan may be the active male, but at the same time he is passively giving in to her charms – falling in love.

In Székely’s compositions, ‘above’ and ‘below’ often have a special significance. The depths belong to the woman. All is well if the man, having drawn up the rules of domestic life, is able to find a safe place above, for instance in the cherry tree. But the depths are always there to lure him away from his duties; from his artistic vocation; from his intellectual, productive life. From early in his career until late in his life, the grave danger of falling is depicted in many of Székely’s works. In most of these cases, falling is not explicitly equated with passion, but Bicskei’s analysis of the oeuvre and careful comparison of the motifs reveals this hidden meaning – not necessarily in individual works, but in their totality.

In the painting known as Nocturne, sculptures in a fountain come alive, gesturing to the young man looking down at them. They are beautiful water nymphs, legendary beings of an irresistible charm. They embody uncontrollable sensuality and desire; everything opposed to orderly, male intellect. An eternal longing that, in the end, cannot be tamed by resorting to stereotypes; it cannot be ordered and structured. No matter how naive young painters, world-savvy French lithographers, or 21st-century women’s magazine columnists try to analyse it, love escapes all categorisation like the elusive water nymphs of old legends. Its general and ‘universally comprehensible’ depictions can only serve as unsettling reminders of what can never be fully told.

* Bicskei, Éva, Ámor és Hymen: A fiatal Székely Bertalan szerelmi történetei [Amor and Hymen: Love Stories of the Young Bertalan Székely], Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2010.

All of your posts require close reading and I will probably return to this one again. I enjoyed it very much. Partly I like the biographical aspects of it, but also the explanations of the art and how relevant they are to ordinary life. New love always seems personal, unique, and even irrational – no one has ever experienced anything like it, or so we believe. Some people maintain relationships that are unique to them, but so often they soon become more a reflection of societal norms, moving from personal to public. I hope I didn’t completely miss your point 🙂 As always your post is thought provoking. The art is lovely as well. Thank you for the time you put into these posts.

Thank you for your kind comments, Susan! I’m glad you liked the post, and your summary is really apt!

I was redirected here from the post ” A Baedeker of the Soul”, which I’m currently reading. I glanced through it and will read it later, but let me just say: projecting an illustrated life of Caravaggio in 1859?! Crazy ahead of his time! Is anything else known about this? Are there more illustrations? I’m more than (pleasantly) surprised and want to know more by all means!

It is a project that was never lithographed, and consists of 11 illustrations altogether. It is a very exciting story – love, murder, prison. It ends with his death. The individual scenes are listed in the book I cited – if you are interested, I can list them for you. Otherwise, I don’t know if there is anything else known about the series, but I can ask the author.

I’d be grateful if you did (if it’s not too much to ask)! I’m very much interested in the reception of Caravaggio during the nineteenth century. Do you have my email?

OK. 🙂 Please send an email to hungarianarthist@yahoo.co.uk, and I will write to you as soon as I can.

Pingback: The Auffindung of the corpse Ludwigs II. of Hungar, ,Bertalan Székely | irina es un robot