In the 1850s, the Hungarian politician Bertalan Szemere was living in emigration in Paris. He was a republican, and had been prime minister of the revolutionary government during the Hungarian War of Independence against Austrian rule in 1849. To avoid being executed, Szemere fled the country after the defeat of the Hungarian army, leaving his beloved wife, Leopoldina, and their children behind. Leopoldina had to face an excruciating wait before the government granted her a passport, and when she finally arrived in Paris, she was stricken by a long illness. Recovering eventually, she gave birth to a girl: Irénke. Life seemed to offer quiet, homely pleasures to the emigrants. In Hungary, Szemere had been a busy politician who spent most of his time away from his family – now Irénke was with him all the time. He saw her first steps, heard her first words, and took endless delight in watching her grow. Then, when she was three years old, the little girl became severely ill and died. The parents were devastated; the pain was unbearable. Szemere wanted to write it all down, to pour all his grief into a sorrowful piece entitled Memory of Irénke, but he failed – it was impossible to express all that anguish. Almost two years later, he tried again. As he explained in his diary: “I have been meaning to write this piece for a long time, but I was afraid to tear up my wounds. I was waiting for them to heal. Readers prefer beautiful pain to actual, real, bleeding pain. The writer is like the painter, who has to follow certain rules when depicting a shipwreck in order to produce an effective painting. Of course, I want to write nothing but how I truly felt at the time, but I know great suffering is more attractive if veiled. The pain I feel now is different from what I felt then – then my wound was shedding blood, it burned, it was ablaze – now it is a scar and only smarts if I touch it. Hence, I am just a distant onlooker myself, and this state of mind is much better suited to describing our feelings to strangers.”*

This post is about an artistic current that did just what Szemere described: it took overwhelming feelings, endless yearning, burning passion, all the bruises that won’t heal, and turned them into sweet, sentimental pictures and poems, easy to digest and to like. This current, known today as the Biedermeier, has been defined in many ways by scholars; I will only cite one of the definitions now. The literary historian Virgil Nemoianu identified the Biedermeier as late Romanticism: a current that “tamed” Romantic excess, fitting it into the mould of everyday life.** If Romantics longed to travel unattainable distances to imaginary worlds, the Biedermeier suggested they visit ‘exotic’ Eastern countries. If Romantics yearned for an ecstatic kind of love that dissolves the soul in a transcendental union with another, the Biedermeier worshipped the home and the family. If Romantics strove to find the common, fundamental mythology of mankind, the Biedermeier discovered local folklore. If Romantics fought for universal freedom, the Biedermeier focused on the nation. By exploring the heights of imagination and the depths of the soul, Romanticism expanded the range of subjects available to artists; the Biedermeier, in turn, projected these onto a small, familiar world.

It would be easy to mock this as petty short-sightedness. The truth is, however, that those lofty, Romantic ideas – ideas about freedom, love, and art – are, indeed, manifested in the simple realities of everyday life. Otherwise, however magnificent, they would not be worth fighting for. And there is something else too. The Biedermeier emerged around 1820, after the Napoleonic Wars. The people of Europe had seen a huge cataclysm; they had seen great ideas rise and fall, discredited by their exploiters; they had seen powerful men tumble. Playing their own walk-on parts in the drama of history, they had been standing in the storm, defenceless and scared, pushed around by great powers. They did not want the drama. They wanted their own little world; a world with no alarms and no surprises.

At the same time, they knew how precarious it all was. They knew that alarms were inevitable, and their familiar little world could collapse in an instance. The storm may have subsided, but the power was there, watching over the subjects of the Austrian Empire. Its presence could never be forgotten.

Pre-1848 Austria was a land of ambivalence. On the one hand, industrialisation and the advent of capitalism had brought great social changes, leading to the emergence of a new middle-class: the bourgeoisie. On the other hand, the setting for all this was a strictly governed absolutistic state, where independent endeavours were under constant scrutiny. Chancellor Klemens von Metternich maintained a secret police with a wide-reaching net of informants, as well as a system of strict censorship. Censors stationed at post offices even read and sometimes destroyed private correspondence, in order to extinguish all sparks of rebellion before they could ignite susceptible hearts. Nevertheless, civic charities and societies, so important for the development of the modern public sphere, were coming into being one by one. People were busy creating their little worlds, taking a quiet life, but furnishing it as comfortably as they could. Hungary, a part of the Habsburg Empire at the time, was no different. It had its own land assembly and some brand new national cultural institutions, but it was under surveillance by the same watchful eyes. The Hungarian and Austrian art world was inseparable, and this symbiosis is manifested in the Biedermeier style.

What was that style like? Maybe the easiest way to describe it is through two seemingly antithetical characteristics: its acute attention to detail and its adherence to a set of general rules, recurring themes, forms, and compositional schemes. Painters revelled in small details, but filtered them through devices of generalisation, which made sure the images were clear and comprehensible. Having already seen a number of similar pictures, one will recognise the subject quickly and will be able to understand the message. Biedermeier images of everyday, domestic subjects (so-called genre paintings) usually had a moral – a simple message along the lines of “Children are pure and innocent” or “Motherly love is endless.” Moulded into preexisting compositions and tagged with these sensible messages, veiled in generalisation and aestheticised, even subjects like the death of a child could be depicted with a certain elevated detachment.

Children and the family were among the favourite subjects of the Biedermeier. Until the late eighteenth century, children were regarded as undeveloped humans who only became interesting as their minds matured. The Romantics, however, were fascinated by states of mind that were not “average” and regarded children as mysterious creatures, unfettered by the rules of society. Taming this exalted view of childhood, the Biedermeier represented children as interesting in a cute and cuddly way. It created images of the ideal home where children were taken care of and loved by their parents, especially their mothers.

József Borsos: Motherly Care, 1845 (location unknown, reproduced from the 1920 catalogue of the auction of the Ernst Museum, Budapest)

Above, I have hinted at the fact that the Biedermeier was – in certain ways – connected to the emergence of the bourgeoisie. Rising demand on part of members of this new class catalysed the production of small-scale paintings that could decorate the walls of modestly furnished middle-class rooms. The new subjects that gained increasing popularity were taken from their lives. Buying art provided them with a way to represent their own identities. The subject of the caring mother is a perfect example: aristocratic mothers gave their babies away to wetnurses, working-class and peasant women, on the other hand, did not have the leisure to focus all their attention on their children. This was supposed to be the specialty of middle-class women.

Painted in 1844, Motherly Care by József Borsos is now only known from a black and white photograph (it last surfaced at an auction in 1920), but its exquisite beauty shines through. Borsos, a Hungarian painter who worked in Vienna from 1840 to 1860-61, excelled at painting opulent surfaces and glittering objects. The mother is shown in a wealthy, but not extravagantly furnished home, surrounded by valuable things, their details painted with the same gentle care with which she tends to her baby. It is the image of a small, warm, and self-contained world. It seems impermeable, unfazed by the tensions inherent to the new social structure.

It would certainly be possible to interpret pictures like this as reflections of a selfish clinging to material possessions and social status. Possible, but also unfair. There was more to the Biedermeier than smug bourgeois self-representation. Besides showing (off) what is ours, these pictures also show what we could lose, or have already lost, or what could be ours, but never will be – and here I am not referring to material possessions. In The Widow, Borsos depicted a woman whose husband had died in the war. She is one of the nameless people whose happiness has been destroyed by the machinations of higher powers, and in this respect the question “Which war?” is of no significance. (It could be the above mentioned War of Independence – but in any case, it has to be noted that she is clearly the widow of an Austrian soldier.) The abundance of tangible details in the painting only underscores the fact that its real subject is someone who is not there; someone who can never be touched again. In its generality (this subject matter was quite common in Biedermeier painting) the picture is a memento to the fact that these things can and do happen. Happiness, then, has to be recorded meticulously, because the next day it may be gone. This feeling, in my opinion, is crucial to the Biedermeier. The melancholy of hearts full up like a landfill.

This is how generalisations worked – but at the same time, Biedermeier painting was also about something that cannot be generalised: the home. The country, the city, the street, the house, the room. That specific one. In 1877, Rudolf von Eitelberger, the first professor of art history at the university of Vienna, who had been an art critic in the 1840s, described this specificity as the most important characteristic of pre-revolutionary Viennese painting, explaining it with the political situation of the time.*** Austria was so isolated, so secluded during the Metternichian regime, that – instead of travelling and picking up foreign influences – its artists had to work with what was available to them, painting their own surroundings in meticulous detail. Political oppression produced a kind of idiosyncratic, naive naturalism, in Eitelberger’s view.

This explanation is somewhat exaggerated. Austria was not completely isolated from external influences: artists did travel abroad, and they could also discover the imagery of European art through imported prints. Still, Eitelberger’s characterisation of the stifling atmosphere of the time cannot be doubted. If thoughts and imagination are restricted, if they cannot venture outside a certain place, a certain set of rules, a certain ideology, they will still wander – and they will wander around the space that is theirs to roam. Their home. They will explore it from every angle, lovingly caressing its details. They will notice what is hidden from the soaring eyes of the Romantic.

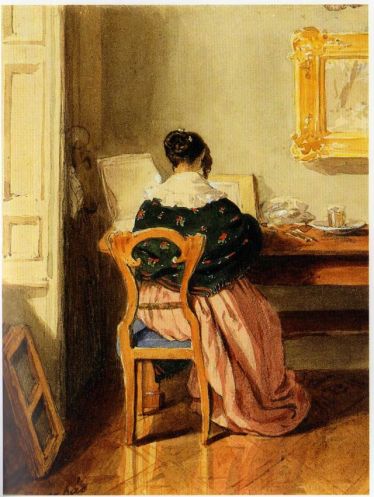

Miklós Barabás, the sober, diligent master of Hungarian Biedermeier, had a good eye for such details. In one of his watercolours, he depicted his wife, Susanne Bois de Chesne, at home. Above, I have said that genre images of the Biedermeier usually fitted their subjects into general schemes. This is just what Barabás did: figures seen from the back, in a room or outside, in silent contemplation or immersed in work, were common in the imagery of German and Austrian Romanticism and Biedermeier. But, on the other hand, this is not just a general woman. It is Susanne, working away on a watercolour, in her own room, surrounded by her own objects. The interplay between general and personal might remind my readers of a previous post: Bertalan Székely’s quest to represent his personal experiences in universally comprehensible images of love and family life. Generalisation helps us relate our unique experiences to others. My home is like that of a middle-class person, who is modestly well off, and my wife is a gentle, industrious woman, who likes to spend her free time in a productive way, creating something pretty. She is the spirit of our home, as one would expect from a decent bourgeois wife.

By evoking these well-known, general statements – which constitute the ‘moral’ of the image – Barabás could say something about his wife and his home to outsiders who never knew her – even to us, strangers peering into their room almost two hundred years later. But how about the details? What did the painting on the wall show? Was it painted by Barabás? Did it have a personal significance? And the painting utensils? Did they belong to Susanne, or was she using her husband’s brushes? Is she really painting a watercolour herself, or is she looking at her husband’s work while he is taking a rest? How about the chair? Was it comfortable? And her clothes? Was this her favourite scarf? Or was it something she carelessly put on at home if she was cold?

Describing your home to outsiders is a daunting task. Generalisations are simple to do, and will work to a certain extent. But your home is a place where you know all the details so well that, to you, they will never be covered by any generalisations, however heartfelt they might be. I am sure Barabás could have added an endless amount of details to his picture of Susanne, but his artistic sobriety, his Biedermeier aesthetics made him refrain. The singularity would not have been captured anyway. A careful depiction of your room will of course be understood as a room, a cozy room even. A sufficient amount of details will distinguish it from other rooms, and the beholder will start to see why it is different. But no matter how much detail you add, no one will ever really understand what it means to you. No one will understand how much it would hurt to lose it.

Here lies the melancholy paradox of the Biedermeier, the paradox of details and generalisations. Of course, I am well aware that I am using an overly simplified, naively realist concept of artistic representation in order to make my point. A painting is not an accurate reflection of reality. For all we know, Susanne might not even have had a green scarf, that painting might not have been hanging on the wall, and she might never have sat at that desk, busy with watercolours. But in the world of the Biedermeier, that does not change anything. What these pictures show is a reality and an ideal at the same time. Memories of bygone happiness merge with quiet hope for future bliss, grief with desire, nostalgia with yearning. It is possible to feel an unsatisfied longing for things we already have, because their possible loss is always lurking somewhere on the horizon.

Seen in this way, the urge to record all those trifles of everyday life does not stem from self-satisfaction, but from something else. In the still, but menacing atmosphere described by Eitelberger, all those details had to be captured precisely because they were not stable – because they were fragile and threatened. At a time when the walls had ears, the small world was not self-contained, and homes were not impenetrable. They were not safe. Their images were projections of wishful thinking; images of an imaginary world that could serve as a safe retreat.

Such a pretty house and such a pretty garden.

Erasmus Engert: Viennese Domestic Garden, 1828-1830 (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin) Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Biedermeier searched for everyday beauty obsessively. Moments of happiness that have passed as soon as we notice them. Moments of sorrow that carry pure beauty in their truthfulness. In times of disillusionment, these things have to be cherished; catalogued, if that helps: pinned to the wall like helpless butterflies in an entomologist’s collection. Bertalan Szemere’s love for his little daughter. Mrs Barabás’s pleasure in watercolours. Sudden moments of complete harmony in old friendships. New friendships born in distress. An imaginary reconstruction of the dazzling colours in Borsos’s lost painting. Blossoming feelings in a short-lived love affair. Idealised memories of a quiet life before the storm hit. Dainty things, easily crushed. Things worth living for.

In everyday life, Romantic passion is subdued, rationalised and aestheticised, but that does not mean it is not sincere. The effects of all those things the Romantics rebelled against – the constraints of society, political oppression, general narrow-mindedness, the futility of the search for eternal harmony between two human beings – cannot be grasped in their totality, but they are manifested in the personal tragedies of those around us. You see them, listless, broken, and hopeless. You want to scream, want to embrace them all in a hug, you want to curse the skies. Instead, you try to comfort them, to smile, to rationalise, to have cheerful conversations, to find ways to live with it. You get a coffee, get a beer. You resort to the Biedermeier.

You see beauty, love, and tenderness more clearly than ever before.

* Szemere, Bertalan, Napló [Diary], ed. Albert, Gábor (Miskolc, 2005), p. 261. (February 1856)

** Nemoianu, Virgil, The Taming of Romanticism: European Literature in the Age of the Biedermeier (London and Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984)

*** Eitelberger v. Edelberg, R[udolf], ‘Das Wiener Genrebild vor dem Jahre 1848,’ in Gesammelte Kunsthistorische Schriften I. (Vienna: W. Braunmüller, 1879), pp. 37-60. (originally published in 1877)

(This post contains quotes from the song No Surprises by Radiohead.)