The novel is the “official Baedeker of the soul,” the Hungarian writer and literary historian Antal Szerb remarked in 1936.* Or should we say it is its Lonely Planet guide? Novels – and other artworks – have the power to take us to corners of the human psyche where we would be afraid to venture on our own. They also show us that these dark and scary places are in fact not so far from places we visit every day: our fears and freak outs lurk beneath the most mundane facets of our existence, disguised as rational responses to human interaction. Longing to welcome other people to our lonely planet, we are at the same time terrified of them getting a glimpse of what we do not want to show. For this reason, we play games. Innocent games designed to obscure the way to our souls. Manipulative games that provide us with the illusion of being in control. Keeping distance within the greatest intimacy gives us a certain kind of comfort – so those distances have to be travelled cautiously. Besides setting up fingerposts on these journeys, art reminds us that our frivolous games can sometimes turn serious – which is why we need our trusted Baedekers in our hands.

The figure of a girl who played with her lover “as the cat trifles with the mouse” became iconic in 19th-century Hungarian culture. Abigail Kund is the tragic heroine of János Arany’s 1877 ballad Call to the Ordeal (Tetemre hívás).** As I will soon explain in detail, Abigail did something we all do to each other every day with less tragic consequences: while playing her game, she touched on a nerve; she pushed a button that released her lover’s fears and insecurities. I have to say, however, that the idea for this post came to me after reading a present-day American bestseller, Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. That novel – maybe the scariest Baedeker ever – tells the story of a couple who know each other the best in the world and yet do not know each other at all. It exaggerates those innocent games into a murder mystery. Getting closer to another person is a thrilling but all in all scary experience, and this book catalogues and entangles all the strategies people use to cope with it. We try to fit the other person into a mould we have created for them – because it is so much easier to find our way among preexisting stereotypes than among the many spurious traits of a real, individual personality. (This is how the painter Bertalan Székely tried to preconceive his marriage in neat little pictures presented to his wife-to-be.) We get annoyed – and insecure – if the other person does not comply. We expect them to know us inside out and to read our minds, but feel threatened if we find that they do. We imagine relationships in terms of power relations and believe that showing our feelings for the other person makes us weak and vulnerable – it means conceding control to them. Games help us retain control – at least that is how Abigail saw it.

In 1881, a young painter, Jenő Gyárfás (1857-1925), sent a large-scale canvas to Budapest as an entry for the grand prize awarded by the National Fine Arts Society. Gyárfás had studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and had subsequently returned to Transylvania, to his hometown Sepsiszentgyörgy (today Sfântu Gheorghe, Romania), to finish his chef d’oeuvre. The jury awarded him with the prize and commended him as a “very promising talent” who had created his masterpiece in seclusion, far from the bustle of the metropolitan art world, using local people as models.

The aim of the Society and its prizes was the support and promotion of national art. Much had changed since the early 19th century: Hungarian art life was flourishing, its institutions were in place, many young artists were studying at Europe’s best academies and returning as accomplished masters. The establishment of a school of national art was still a central concern, but expectations were more relaxed: as many works of high quality were produced each year, the ‘Hungarianness’ of their subject gradually lost its central significance. Nevertheless, the subject matter of Gyárfás’ picture would have been considered ‘national’ even by the strictest mid-century critics: he not only chose a scene from a poem by a great poet and public figure who was by then turning into a national icon, but that poem was a ballad that recounted a supposedly ancient Hungarian custom (the ordeal of the bier), while imitating folk ballads. In the second half of the 19th century, as the influential movement of literary populism became prevalent, the life and lore of Hungarian peasants was considered one of the most profoundly national subjects (along with Hungarian history) – this is why the Art Society jury praised Gyárfás for using people from the vicinity of his native town as models. Arany’s ballad – and Gyárfás’ picture –, however, engaged with folk tradition freely and chose the human soul as their main subject. The games we play to hide our feelings, our needy ways of forcing others to show theirs, the damage we cause, and the unbearable guilt we feel.

Arany’s poem starts as a murder mystery: a young man, Benjamin Bárcz (Benő Bárczi in the original) is found dead in the forest, a dagger in his heart. In order to find the killer, his family revives the ancient custom of the ordeal of the bier: the dead body, which is supposed to start bleeding when the murderer is near, is laid out in their castle, and everyone Benő knew is called to the bier one by one – his enemies, his friends, his acquaintances, even his mother and sister, and – finally – “his darling bride, fair Abigail” – on whose arrival the blood starts flowing in streams.

In Gyárfás’s painting we see Abigail gripped by maddening guilt, dancing down the stairs while everyone else watches in horror. She did not kill Benő, she says. She merely placed the dagger in his hands. He should have known very well that I love him, she says, but he urged me to say it – otherwise he would kill himself.

Abigail did not say those words. Instead, she playfully gave him a dagger. Go on, she said.

Behold the story of a woman who thought declaring her love would mean losing the game – and losing herself. And of a man who, driven by his own insecurity, wanted her to show her feelings in a way she was uncomfortable with, so much so that it made her turn to deadly cynism. Gyárfás made many careful studies for the faces, especially that of Abigail, to be able to convey the guilt, the dread, the pain of the realisation that needy nagging and frivolous games can lead to such a devastating effect. He used all the skills he had acquired at the Academy in this monumental work. In the manner of a history painter, he created many sketches for the composition itself before he settled for the final version. He made lots of studies after live models, carefully grouping the figures in the composition to convey different emotions and reactions – another centuries-old device of history painting. At the same time, his naturalistic treatment of the figures, his detailed representation of their skins and their clothes is typical of Munich genre painting of the time, and, as noted above, his figures were perceived as rural characters – that is, typical characters of genre painting. By blurring the boundaries between genres, Gyárfás was making it clear that he was not representing a unique historical event, but something universally human; something every individual can relate to. At the Hungarian National Gallery, 19th-century history paintings have been shown together for decades, creating a narrative not only of the history of this type of picture, but also of the history of the Hungarian nation – from a 19th-century point of view, of course. But Call to the Ordeal was always shown in a completely different space, surrounded by Gyárfás’s sketches and other works from the late 19th century, as part of an art historical narrative.

Call to the Ordeal is not the only one among Arany’s ballads that tells the stories of human beings doomed by their own weaknesses – their moral failures, unrestrained passions, or simple bad judgement. These brilliant poems merge folklore and history with deep insight into human nature, very often thematising the torments of a guilty conscience. The ideology of literary populism described folk poetry as the reflection of the supposedly pure and straightforward minds and souls of Hungarian peasants, who were stereotyped as “simple” children of nature, in contrast to the oh-so-subtle people of the city. Poets were expected to imitate that supposed simplicity. To Arany, however, the folk ballads he studied revealed much more complexity. Inspired by them, he wrote poems that show people – whether they are kings or peasants – as anything but simple and straightforward. It is possible to link these texts to the tradition of the Gothic – a tradition that was, as I have aimed to show in a previous post, excluded by the dominant narrative of national art, but lived on as an undercurrent that constantly challenged it. The motif that Arany’s ballads share with the Gothic tradition – which spans from 18th-century Gothic novels to present-day crime shows – is the miserable fragility of human beings, both in a moral and a physical sense. They are easily led astray by passion or vanity, hopelessly susceptible to temptation, and their bodies are so easy to destroy that it can happen in the most trivial accident. They cause and suffer fatal injuries due to their flaws, and break down under the terrible consequences. In Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, the protagonist, blinded by passion and lust, stabs and kills his own daughter by mistake. In an episode of CSI (season I, episode 5, to be precise) a boy kills his best friend in the desert, while they are both under the influence of a hallucinatory drug. In Call to the Ordeal… well, we know.

The illustrations created by various artists for Arany’s ballads are some of the most Gothic images in 19th-century Hungarian art history. Mistress Agnes tells the story of a woman who conspires with her lover to murder her husband, but goes mad with guilt after the deed, manically washing bloodstains from her bedsheets “from year’s end unto year’s end, / Winter, summer, all year through,” until she grows old and the sheets turn into rags.

Bertalan Székely depicted Mistress Agnes, the madwoman, in an icy winter landscape, dishevelled, ragged, and scary. The wooden board behind her is reminiscent of an old gravestone. Mihály Zichy drew her in her prison cell, surrounded by ghosts conjured up by her own guilty conscience.

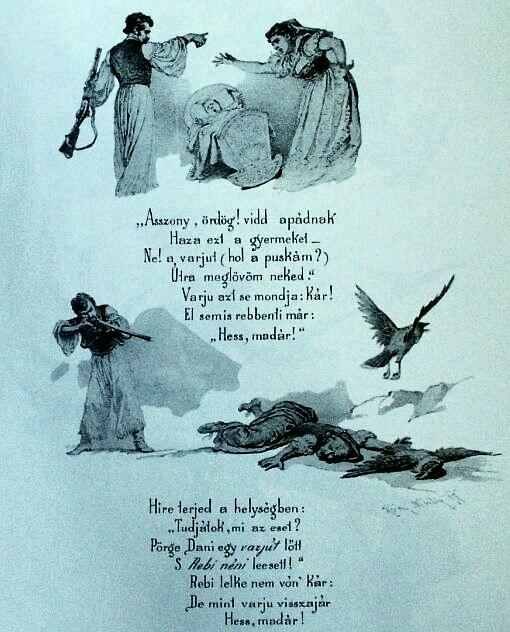

Gothic tales often involve the supernatural, but in many cases as a projection of human frailties. In Arany’s Vörös Rébék (Red Rebecca), a young man, Dani, marries a vain and flirtatious girl on the advice of Rébék, the witch, who then goes on to persuade the wife to cheat on her husband, wrecking the life of the family. The husband throws his wife out, shooting a crow for her to eat – but the bird proves to be no other than old Rébék who had been spying on them in animal form. When the crow is shot, the spell dissolves, and the old woman’s corpse falls from the tree. Dani is wanted for murder and has to flee. Encountering his wife’s lover on a bridge, he pushes him into the stream, thus becoming a real murderer. He spends the rest of his life in hiding, pursued by hungry crows who can hardly wait to get their revenge on his dead body.

Mihály Zichy: Illustrations for János Arany’s Vörös Rébék, 1892-1897 (Photo: www.bibl.u-szeged.hu)

In these stories, it is not the supernatural that is scary, but the flimsiness of human character, which can lead to catastrophes without any outside intervention. Who needs witches like Rébék when people are perfectly capable of ruining their lives on their own accord? Dani chose the wrong woman because the witch convinced him. Oh, of course. His wife cheated on him because Rébék told her so. Yes, definitely.

Blaming the witch is a way to explain irrational human behaviour, just as hiding our feelings, nagging needily, or playing our games are ways to cope with the irrationality, or at least to minimise its consequences on our lives; its potential to hurt us. As shown by our Baedekers, these coping strategies can strike back with a vengeance. Still, we cling to them. Dangerous but inevitable, they are our pathetic, desperate, and sometimes tragic ways of getting by.

Mihály Zichy: Illustration for János Arany’s Call to the Ordeal, 1894-1895 (Photo: http://www.bibl.u-szeged.hu)

* “[In the 18th century] the novel became the official Baedeker of the new, exotic land: the soul.” Antal Szerb, Hétköznapok és csodák: Francia, angol, amerikai, német regények a világháború után [Weekdays and Wonders: French, English, American and German Novels after the World War], Budapest: Révai Kiadás, 1936, pp. 15-16.

**In this post, I am quoting from William N. Loew’s translations.